PATHOGEN INACTIVATION

Protects Patients From Viruses & Emerging Pathogens

The next pandemic is only a matter of time

Over the last decade, the emergence of several zoonotic viruses has demonstrated that previously unknown or neglected pathogens have the potential to cause epidemics and therefore to pose a threat to global public health. Even more concerning are the estimated 1.7 million still undiscovered viruses present in the natural environment or “global virome,” with many of these as-yet uncharacterised viruses predicted to be pathogenic for humans.

Lawrence P et al., 2023

The natural virome and pandemic potential: Disease X.

Curr Opin Virol 63: 101377

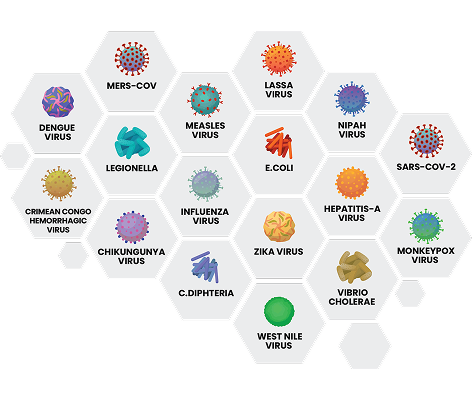

New (re)emerging infectious disease agents at the doorstep

In recent decades, all over the world there have been outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases (EID). Considering existing changes in the epidemiology of communicable diseases, the increase in international travel and trade as well as the projected climate-change, which favours the geographical spread of the vectors, the risk of infection transmission from arthropods, such as mosquitoes, in many countries will increase. Consequently, the safety of blood transfusion will increasingly be at risk.

Arbovirus-infected donors are often asymptomatic

The spreading of vectors is increasing due to climate change

Globalisation and travel increase contacts

European centre for disease prevention and control

Learn more about the current known distribution of invasive mosquitoes in Europe

Recent outbreaks and transmissions

Disease outbreaks pose a risk to blood safety and supply

Due to the increasing frequency and diversity of EID outbreaks, the traditional response of additional blood donation screening tests and deferring more donors is limited by concerns of cost-effectiveness and feasibility. This reactive approach calls for a re-evaluation of current practices. There are not only quantitative limits to screening and deferring, but also conceptual challenges. These so-called “new pathogens” may disseminate widely through transfusion before being recognised and before a screening test can be developed and implemented and, even in the presence of a test, emerging outbreaks can adversely impact blood availability.

A continuing “add-on” strategy is unlikely to be sustainable

Until the early 1990s, blood products were often contaminated with HIV or HCV, resulting in many transfusion-related infections. Since then, the introduction of elaborate measures has greatly increased the safety of blood products in relation to the transmission of infections.

An impressive battery of screening tests has been put in place to secure the safety of the blood supply: a combination of general screening, seasonal screening and selective testing. But even though this already large and still ever-increasing panel of tests exists, not all are currently being performed due to cost and logistical constraints.

But testing is a reactive strategy; cases of transfusion transmitted infections (TTIs) are likely to occur before the implementation of a new test. Despite all efforts and increased costs, the risk for transmission has decreased but it is not ‘zero’. Every test has a limit of detection and viral loads below that limit can be sufficient to cause infection. The INTERCEPT™ Blood System is an additional line of defence which can inactivate infectious disease agents present at low titres that otherwise could escape detection with current testing methods.

Get ready today for the next blood borne safety challenge

From a reactive to a proactive blood safety strategy

The INTERCEPT™ Blood System has demonstrated its benefits during several outbreaks of arthropod-borne viruses and is now recognised as a major asset to minimise the risk of TTIs in future emerging and EID epidemics. Experience in using INTERCEPT™ Blood System during infectious disease outbreaks has shown that, if INTERCEPT™ Blood System is already in routine use, the time to switch on or scale up the use of this technology in an affected area is shorter than it would be if it was not already established.1,2,3 This gain in time may allow for production of sufficient pathogen inactivated blood components to cover the local demand. Real-life experience has shown that such centres which have already established the method can provide for other centres which have not yet done so.

You may also be interested in

References:

- Rasongles P et al., 2009. Transfusion of platelet components prepared with photochemical pathogen inactivation treatment during a Chikungunya virus epidemic in Ile de La Réunion. Transfusion 49: 1083-1091

- Marano G et al., 2017. Ten years since the last Chikungunya virus outbreak in Italy: history repeats itself. Blood Transfus 15: 489-590

- Domanovic D et al., 2019. Pathogen reduction of blood components during outbreaks of infectious diseases in the European Union: an expert opinion from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control consultation meeting. Blood Transfus 17: 433-448

There is no pathogen inactivation process that has been shown to eliminate all pathogens. Certain non-enveloped viruses (e.g., HAV, HEV, B19, and poliovirus) and Bacillus cereus spores have demonstrated resistance to the INTERCEPT™ process. For a full list of warnings, precautions for use and pathogens inactivated, please refer to the Technical Data Sheet and Instructions for Use found in the resource section of this website.